Arts Organizations Are Celebrating Milestones, Changing Executives and Planning Expansions.

By Randy Noles

At the risk of stating the obvious, it has been a busy year for local arts groups. Not only are most bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels of support and attendance, many are also celebrating anniversaries, welcoming new leaders and planning major moves. The downside: All the activity comes as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis vetoed $32 million in arts spending from the legislature-approved 2024–25 budget. This wiped out funding for all arts grant programs administered by the state Division of Arts and Culture, which in turn impacted 864 nonprofit organizations statewide (including 89 in Central Florida). But, as the following story demonstrates, the local cultural community remains resilient and vibrant—and determined to continue elevating the region’s quality of life and serving as a major economic driver even as unanticipated challenges and hurdles make those jobs much more difficult.

BACH FESTIVAL SOCIETY OF WINTER PARK

Iconic Event Marks 90 Years with Gusto

In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law; the “Black Sunday” dust storm displaced an estimated 300 million tons of topsoil in New Mexico, Colorado, Texas and Oklahoma; Babe Ruth hit his 714th and final career home run at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh; and the most popular recording artists were Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby.

Also, on the campus of Rollins College, a group of musicians performed Bach’s Mass in B Minor in Knowles Memorial Chapel. This event, organized by snowbird Isabelle Sprague-Smith, an educator and philanthropist from New York, was Winter Park’s first Bach Festival. It would not be the last.

At the urging of then-President Hamilton Holt, a committee of professors and community leaders formed a Bach Festival Committee in 1937 “to present to the public for its enlightenment, education, pleasure and enjoyment musical presentations, both orchestral and choral.” The organization was incorporated in 1940 as the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park.

So, to be precise about it, 2024–25 marks the 90th season of the Bach Festival itself—which will run from February 15 to March 2, 2025—and the 85th anniversary of the Bach Festival Society, which presents musical programming virtually year-round.

Amazingly, Artistic Director John V. Sinclair wasn’t around for the first Bach Festival concert or for the first organizational meeting of the society under whose umbrella it operates. That, of course, wouldn’t have been possible for someone who wasn’t even born until 1954.

However, most locals can’t remember a time when the society’s creative force was anyone other than Sinclair, who is marking his own anniversaries: 35 years with the society—which today encompasses a 180-voice choir and a full orchestra—and 40 years as director of music at Rollins.

(Although the society is a fully independent nonprofit, it maintains its historic partnership with the college, which hosts performances at Knowles Memorial Chapel and the John M. Tiedtke Concert Hall, both at the college, and Steinmetz Hall at Dr. Phillips Center.)

“This is a year where I thought we should remember who we are,” says the energetic Sinclair, who is arguably whomever the classical music equivalent is of the hardest-working man in show business (apologies to James Brown.) “Every anniversary year, we go back to the three B’s: Bach, Beethoven and Brahms.”

With Sinclair, though, you can always expect the unexpected. In addition to welcoming back some of the most popular visiting artists in recent years, this season he’ll offer everything from classical music by unjustly forgotten composers to spirituals with big-band arrangements to heartwarming holiday concerts.

Post-festival highlights include a concert by the Bach Chamber Singers, who’ll present selections from works that will be performed in full over the next three years. There’ll also be two recitals: one by alumni of the choir and another by virtuosos in the orchestra.

Later in the year look for the 1st Annual Bach Festival Society American Oratorio Competition, which Sinclair believes will immediately become the largest oratorio competition in the country. “We’re the perfect organization to do this,” he adds.

The program is geared toward young professionals looking to launch their careers, comparable to the breakthrough-seeking opera singers who participate in the Metropolitan Opera’s annual Laffont Competition. (Laffont regionals were held earlier this year in Tiedtke Hall.)

The society expects between 150 and 200 applicants, who will submit their works online. Finalists will be announced in December and will travel to compete in Winter Park. Winners will receive financial prizes and the guarantee of solo professional engagements with the Bach Festival and, for first-place winner, the Messiah Choral Society of Orlando.

Raised in Independence, Missouri, Sinclair—who is usually called “Doc,” by his friends and colleagues—is a graduate of William Jewell College a Baptist-affiliated liberal-arts institution in Liberty, Missouri, where he earned an undergraduate degree in music.

Then it was off to the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s Conservatory of Music and Dance, where he earned master’s and doctoral degrees in music education with an emphasis on conducting.

After graduation, Sinclair worked as a middle-school choral director in Belton, a suburb of Kansas City, in part to be near Gail Duvé, his high-school sweetheart who was completing her English degree.

The couple married in 1977 and both got jobs teaching high school in Sedalia, Missouri. After graduation, John became director of choirs at East Texas Baptist University in Marshall, Texas, and Gail taught high-school English before the Rollins job opened and they relocated to Winter Park.

These days, Sinclair routinely conducts about 150 performances a year in addition to his work as a teacher and a department head. He also serves as music director of the First Congregational Church of Winter Park; director of the local Messiah Choral Society; and conductor of the International Moravian Music Festivals.

Perhaps Sinclair’s most high-profile engagement is as one of two conductors during Epcot’s multi-performance Candlelight Processional, where in 2022 he was celebrated for leading his 1,000th holiday performance at the attraction’s America Gardens Theater.

When it comes to the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, though, Sinclair is quick to credit others for their contributions. In particular, he points to the legendary John M. Tiedtke, a philanthropist (and music-lover) who served as the society’s president from 1950—when Sprague-Smith, the founder, died—to 2003.

Just before Tiedtke’s death in 2004 at age 97, he established the John M. Tiedtke Endowed Chair of Music, of which Sinclair was the first recipient. The chair was funded in part by an anonymous $250,000 donation.

That gift was later revealed to have come from Fred McFeely Rogers, Class of ’51, a music composition major who became TV’s Mister Rogers and befriended the Sinclairs during his frequent Winter Park visits.

For the 90th Bach Festival Society of Winter Park season, you can customize your season tickets to include every performance or selected performances. You can also buy tickets for only the Bach Festival itself in February. For more information, call 407.646.2182. or visit bachfestivalflorida.org.

CREALDÉ SCHOOL OF ART

Still a Place Where ‘Art Is for Everyone’

Peter Schreyer can look back over 29 years as CEO and executive director of Crealdé School of Art with a sense of pride and accomplishment, as well as confidence that William S. “Bill” Jenkins, the artistically inclined building contractor who founded the school 50 years ago would be pleased at how it has all turned out.

In January, Schreyer—an acclaimed documentary photographer— will transition into the role of executive consultant for community relations for the school while continuing to serve on its faculty and as manager of the photography program.

Emily Bourmas-Fry, director of development for Orlando Museum of Art for 14 years, assumed the role as associate executive director in July and will become CEO after six months of coaching and mentoring from Schreyer. Her experience also includes seven years in creative services and public relations in local television.

Bourmas-Fry—who says one of her primary goals is to further the school’s already robust outreach initiatives—earned a master’s degree in cultural anthropology from the University of Adelaide, Australia. She is bilingual (English and Greek) and holds citizenships in Greece, Australia and the United States.

“I believe in the power of art to bring communities together,” says Bourmas-Fry, who also volunteers for FusionFest, an organization that produces an annual festival celebrating cultural diversity. “I’m confident that we can navigate a seamless transition as I make the position my own, steering the organization toward its next phase of growth and impact.”

Schreyer had already made his mark as a photographer prior to joining the school. Since 1980, his evocative black-and-white images have been showcased in an array of juried and invitational museum and gallery exhibitions across Switzerland—where Schreyer was born—and the United States.

But his accomplishments at Crealdé have profoundly impacted Winter Park by recognizing and celebrating its diversity and multiculturalism. In 2007, for example, the school led a partnership between the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency and citizens of its west side neighborhood, which is historically African American, to found the Hannibal Square Heritage Center.

And in Winter Garden, the school offers classes at the Jessie Brock Community Center on Dillard Street and has forged collaborations with Orange County Public Schools, the Boys & Girls Clubs of Central Florida, the Farmworkers Association of Florida and dozens of other community-based educational and social-service organizations.

In 2009, Schreyer—previously the recipient of a Visual Art Fellowship in Photography from the State of Florida—was named Arts Educator of the Year by United Arts of Central Florida. In 2016, he and the Hannibal Square Heritage Center notched a Diversity & Inclusion Award from the Florida Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs (which is now the Division of Arts and Culture).

More recently, the school celebrated completion of a $425,000 renovation that created five new teaching studios, including a sculpture classroom, a second ceramics studio and dedicated teaching studios for the jewelry and young artists programs.

“People love traditional arts that don’t involve technology or computers, things that can be done with their hands or things that have been based on the traditions of people all over the world,” notes Schreyer, who adds that the ceramics program alone now has more than 250 students.

The project was funded through support from students and members, plus a $75,000 grant from Dr. Phillips Charities and a $100,000 grant from the State of Florida. Winter Park-based construction company E2—whose owner, Rob Smith, attended the school’s art camp as a child—contributed an additional $200,000 worth of in-kind support in materials and services.

A new woodworking and metal-smithing studio is also on the drawing board thanks to the generosity of William “Bill” Platt, a former board member and longtime supporter of Crealdé.

Overall, during Schreyer’s tenure the school’s annual budget has increased from $275,000 to $1.5 million per year, and its programs have grown from serving several hundred to more than 4,000 students annually. Between grants, donations and earned revenue, the school has paid its way through this period of sustained growth without incurring debt.

Something special and creative happens for many different sorts of people almost every day on the busy campus in east Winter Park—and in just about every genre of art.

Instruction is offered in drawing, photography, painting, ceramics, sculpture, papermaking, jewelry design, fabric arts and bookmaking (the legal kind). In all, the school offers more than 125 visual arts classes and humanities-based programs annually.

That eclectic approach would have been fine with Jenkins, a talented painter whose mantra was simple: “Art Is for Everyone.” He founded Crealdé Arts Inc. in 1975 and built the Spanish-style campus, which included an office building that was intended to house artists’ studios. (Today the office building to which the school is attached is under separate ownership and leases space to a variety of businesses.)

It’s said that Jenkins devised the name “Crealdé” by combining the Spanish word crear (“to create”) and the Old English word alde (“village”).

Born in rural Preston, Georgia, in 1909, Jenkins told the Orlando Sentinel in 1988 that he was inspired by childhood memories of quilting bees.

“When the other kids were sick or busy, I didn’t have much to do,” recalled Jenkins, who died in 1996. “So I would go to the quilting bees and listen to the ladies talk as they worked. They had the best time, and so did I.’’ The school, Jenkins added, was in part an effort to re-create that sense of community and creativity.

Jenkins earned a BFA from the University of Florida and traveled to Italy, where he graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Florence. He married Alice Moberg in 1942 and served in the U.S. Army during World War II.

Before Jenkins started his homebuilding business, he worked with the Veterans Administration in St. Petersburg and Tallahassee to develop a pioneering art therapy program for returning GIs. Retrospectives of his paintings have been staged at the school’s Alice & William Jenkins Gallery.

Crealdé’s main campus is located at 600 St. Andrews Boulevard, Winter Park. For more information, call 407.671.1886 or visit crealde.org. The Hannibal Square Heritage Center is located at 642 West New England Avenue, Winter Park. For more information, visit hannibalsquareheritagecenter.org or call 407.539.2680.

ORLANDO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

OPO Builds Audience, Renews Retro Venue

If there’s one thing that fans of the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra can be certain of now that the organization is being run by Karina Bharne —who last October became the first woman to hold OPO’s top administrative post—it’s that they’ll be seeing performances in as many settings and with as many partners as possible.

Bharne was hired in October to replace Paul Helfrich, who after an almost four-year stint resigned to move to North Carolina, where his wife Jessica had been appointed to a full-time position as associate concertmaster with the North Carolina Symphony Orchestra.

“Too often arts organizations operate in silos,” Bharne says. “That’s one thing that impressed me about the Orlando Philharmonic. Here we work together with everybody. And that’s a great thing because we want to share the music whenever possible.”

It’s true that OPO is busy indeed, providing onstage film soundtracks for special screening events and live accompaniment for Orlando Ballet and Opera Orlando.

In all, the orchestra and its ensembles perform more than 170 concerts each year and impact more than 150,000 music-lovers of all ages through performances and community outreach programs.

Conductor and Music Director Eric Jacobsen has curated an exciting 2024–25 season—OPO’s 32nd—that will open in October with a program featuring his Grammy-winning wife, folk singer Aoife O’Donovan.

Also en route this season are filmmaker Jamie Bernstein, daughter of Leonard Bernstein, who’ll moderate a program featuring her father’s immortal music, and Michael James Scott, the erstwhile Orlando theater kid who went on to stage stardom in, among other roles, the Genie in Disney’s Aladdin.

And OPO has essentially completed the first phase of a massive renovation project for The Plaza Live, which was built in 1963 as a two-screen movie theater with “rocking chair” seating. The building was topped by a distinctive spinning spire that beamed “Plaza Theater” and epitomized the national mania for the Space Age.

OPO’s Focus Series and Symphony Storytime Series are held at The Plaza Live, which also houses administrative offices and hosts touring acts as a rental venue. The orchestra’s annual six-concert Classics Series and four-concert Pops Series are held in Steinmetz Hall at Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts.

Bharne, who had served as executive director for Symphony Tacoma in Washington prior to snaring the opportunity in Central Florida, is a well-seasoned arts executive who earned an undergraduate degree in trombone performance and once wanted to be a performer, not an administrator.

“But I decided that performing probably wasn’t a good career move for me,” says Bharne, who recognized that her skills could be put to better use running arts organizations. “I loved music, but just didn’t have those kinds of aspirations.”

She subsequently earned a master’s degree in arts management, with both degrees coming from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. She later notched an MBA from Eastern Washington University in Cheney, Washington.

Bharne did, however, marry a performer. Her husband, Ilan Morgenstern, is a bass trombonist with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra who took a sabbatical to move with his wife to Orlando. The couple has a 2-year-old son, Rahm.

The Tacoma gig lasted five successful years, during which Bharne was selected to participate in an emerging leaders program sponsored by the League of American Orchestras. Also during her tenure, the orchestra was awarded a competitive grant from the league’s Catalyst Incubator Fund for its work on diversity, equity and inclusion.

Prior to that, Bahrne worked for the San Antonio Symphony as director of orchestra personnel and later vice president and general manager. She was also the orchestra’s interim executive director for seven months in 2018. Financial problems had besieged the operation—which finally shut down in 2022—for decades prior to her arrival.

That’s likely one reason why Bharne is so committed to robust fundraising. “My goal is to raise OPO’s endowment to $18 million,” she says, which is ambitious considering that the tally is about $4 million now. “That’s where we should be. One of my most crucial roles is partnering with our philanthropic team.”

Some of the fundraising focus will be on The Plaza Live, which OPO bought—along with its ongoing live concert business—for $3.4 million in 2013. The orchestra spent about $4.5 million on, among other things, building a suite of administrative offices and refreshing a public events space named for Mary Palmer, a former board member and president.

But the pace quickened three years later, when the City of Orlando bought the 903-seat venue for $3 million and leased it back to OPO for $1 per year. Once the orchestra occupied a publicly owned building, it became eligible for a $10 million tourism development tax (TDT) grant that covered the purchase price and left $7 million for additional renovations.

Now the venue boasts new bars, a sleek lobby rotunda, upgraded bathrooms and a comfortable main auditorium with improved acoustics, lighting and tiered floor seating. The marquee is digital (a major aesthetic improvement) and even the spire—which the city designated as a historic landmark in 1997—has been restored and returned to its rightful position.

OPO is still fundraising to help pay for the recently completed renovation and to add a VIP experience room. The “InSPIRE” capital campaign has raised about $1.5 million with another $1 million still needed.

Meanwhile the orchestra is seeking an additional $2.1 million in TDT funds and offering naming rights within the venue at various levels that range from $500 to $25,000.

The Plaza Live (and the OPO box office) is located at 425 North Bumby Avenue, Orlando. For more information about the upcoming season, call 407.770.0071 or visit orlandophil.org.

BLUE BAMBOO CENTER FOR ART

‘The Boo’ Will Move to the Mainstream

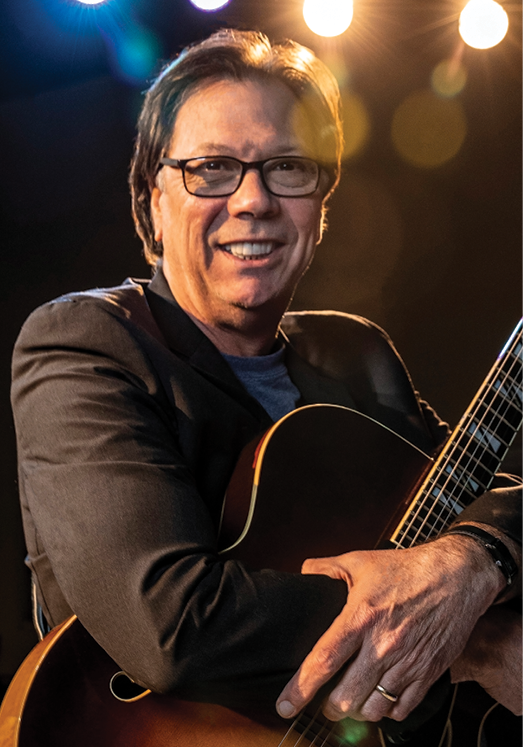

Guitarist Chris Cortez penned a song in the late 1980s about a man with no arms, whom he saw painting with his feet. “It’s not what happens to you, it’s what you do about it,” goes the chorus.

Cortez, co-founder, president and CEO of the nonprofit Blue Bamboo Center for the Arts, lives by those words. He has persevered along the long and winding road of a musical career, no matter what the odds or obstacles.

That determination is perhaps one reason why—against the odds—Blue Bamboo (known as “The Boo” by fans) will make its new home in Winter Park’s former public library building at 460 East New England Avenue.

Winter Park Mayor Sheila DeCiccio had previously invited a competing proposal from Rollins College to use the 33,000-square-foot red-brick structure—which had been unoccupied since the library moved to newly constructed digs in 2021—for the Rollins Museum of Art.

The college had already gotten approval from the city to build a new 31,000-square-foot facility for the museum in the nearby Lawrence Center, but could have renovated and repurposed the old library more quickly and inexpensively.

Cortez, however, argued that the city already had numerous museums but no live-performance venues except the Winter Park Playhouse—which is now working with city officials to determine how it can avoid relocating to parts unknown after losing its lease.

In any case, the presentation by Cortez carried the day by a 4-1 vote (with DeCiccio the lone opponent) during a commission meeting packed with vocal supporters—most of whom spoke passionately about the importance of The Boo, which previously occupied a 6,000-square-foot warehouse hidden away on Kentucky Avenue.

That warehouse, however, was purchased by investors and the rent escalated, forcing Cortez and his wife, Melody, to seek another location. Several seemingly promising possibilities failed to pan out before the library opportunity, seemingly a longshot, presented itself.

At press time a lease with an initial term of 20 years with the option for two 10-year extensions had been approved by the city commission, with DeCiccio again casting the lone dissenting vote. However, an occupancy and construction timeline had not yet been finalized.

“Thanks to the commission and public for all their support,” says Cortez. “The approval [for the lease] was amazing. We’re looking forward to the next steps.”

Those next steps must include a zoning change for the land, which is currently designated for residential use—although it has never been used for housing. The most likely solution would be a change to PQP (public and quasi-public) zoning. Then rules would have to be altered to allow city-owned PQP properties to operate as commercial venues.

Phase One will include making repairs—which need not be as extensive as first thought, says Cortez—and converting the first floor to a performance space with approximately 150 seats. The estimated $486,364 price tag will be covered by board contributions as well as sponsorships, memberships and a construction loan.

Phase Two will include a second-floor recording studio and space for tenants Central Florida Vocal Arts, Performing Arts Matter and Winter Park Chamber Music Academy. Phase Three will make the third floor available, for a nominal fee, to any nonprofit and also include art galleries that will feature work by local creators.

The entire project, once construction gets underway, could take up to three years to complete—although the first-floor performance space could be ready within months.

It’s a tall order, alright, but the smart money is on Cortez, who opened The Boo in 2016 and produced as many as 200 performances annually with artists from every genre imaginable. Several dozen concerts per year have typically been held to raise money for charities.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and the most rewarding,” says Cortez, a Cincinnati native who moved to Orlando at age 2 with his family, including his mother, Virginia “Ginny” Cortez, a founding member of what is now Orlando Family Stage (formerly Orlando Repertory Theatre).

His father, Joe, a Martin Marietta technical writer, gave the talented 9-year-old a $13 guitar and (perhaps inadvertently) launched the career of a jazz player, pop vocalist, record producer and entertainment empresario.

After graduation from Edgewater High School, Cortez played with various Top 40 bands and performed at Walt Disney World, including a regular gig with Kids of the Kingdom. He also played guitar with a jazz fusion group called, prophetically, Big Bamboo.

The combo, which was the house band at a downtown Orlando nightclub called Daisy’s Basement, allowed Cortez to polish his artistry. In 1986, however, he left Central Florida for almost 30 years, during which time he played in house bands, directed music at a casino and produced more than 30 CDs—including eight of his own.

Cortez met his wife, the aptly named Melody—who is now assistant manager of The Boo—in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 2015. The couple opted to return to Central Florida and build a creative hub that could offer top-tier entertainment from veteran touring acts while also nurturing talented newcomers.

Notes Cortez: “I begin with ‘it’s possible’ and everything else is logistics.” Given the way his most recent adventure has moved forward, that’s a hard philosophy to argue with.

While the renovation and relocation challenges are being worked through, The Boo will continue to hold concerts in other venues and recently concluded a series in the Winter Park Library—the new one, that is—with others in the works. For more information, visit bluebambooartcenter.com.

ORLANDO BALLET

Surging Company to Make Its School Elite

Few local arts organizations have built a more distinguished artistic legacy than Orlando Ballet, which was founded in 1974 but can trace its roots to 1947, when Bill and Edith Royal opened a private studio with classes at All Saints Episcopal Church in Winter Park.

Even fewer local arts organizations have suffered through as many near-death experiences as the ballet. But those days of operating on the razor’s edge have passed, thanks in part to the involvement of Jonathan and Krista Ledden—he a retired investment banker and she a former dancer with the Twyla Tharp Dance Company in New York.

Jonathan is president and Krista is director emerita of the ballet’s board of directors. After joining in 2017, they pushed for fundamental operational and philosophical changes that have allowed the often beleaguered (but always beloved) organization to stabilize and grow at a pace that seemed unlikely a decade ago.

In fact, a rejuvenated ballet celebrated a triumphal 50th anniversary season last year that was highlighted by a $3.6 million reimagining of The Nutcracker by Artistic Director Jorden Morris—who is also serving as the ballet’s interim executive director while a national search is underway to replace Cheryl Collins, who resigned from the post in March.

But there’s still work to do. The most recent change is the hiring of Christopher Alloways-Ramsey as the ballet’s education director. He’ll be responsible for the Orlando Ballet School as well as the organization’s variety of initiatives related to community enrichment.

Dancer Shane Bland, previously field director, is now the day-to-day manager of community enrichment, which encompasses such programs as STEPS (Scholarship Training for the Enrichment of Primary Students) designed for second- through fifth-graders from underserved communities. In his expanded role, Bland will report to Alloways-Ramsey.

Says Morris: “We’ve been somewhat fragmented with all that we offer, so it makes more sense to bring together all of our dance training—be it professional or classes for those who just want to learn to dance. The outcome will be transformative and bring more consistent support for everything we do.”

Alloways-Ramsey, a native of South Georgia who earned an undergraduate degree in liberal arts from Harvard University and an MFA in choreography from Jacksonville University, certainly appears well prepared for the task. “I’ve had both a career as a dancer and in academia,” he says. “That’s kind of a hard bird to find in the classical ballet world.”

Most recently, Alloways-Ramsey was an assistant professor at the University of Utah’s School of Dance. Prior to that he served in adjunct teaching roles at Harvard University and Boston Conservatory along with faculty positions at the American Academy of Ballet at SUNY in New York; Boston Arts Academy; and the Utah Dance Institute.

In addition, he served as head of ballet at the Cape Academy of Performing Arts in Cape Town, South Africa, where he oversaw an elite dancer-training program. He has completed American Ballet Theater’s Certification program and in 2013 was awarded a fellowship through the Center for Arts in Education at Boston Arts Academy.

Alloways-Ramsey’s dance career began at age 18 with the Alabama Ballet Theater followed by BalletMet in Columbus, Ohio; Cincinnati Ballet; and Ballet West in Salt Lake City. He joined Boston Ballet in 1994 and concurrently kept up a busy schedule as a guest artist at regional ballets around the country.

He says he expects to incorporate elements of Russian methodology —known for its theatrical style, technical precision, athleticism and emotive storytelling—in the school’s upper levels. And for students who have the talent and work ethic to pursue dance careers he expects to provide a pathway to success.

Says Alloways-Ramsey: “The school will offer greater strategic opportunities for youngsters interested in professional dance, as well as provide a destination for locals who simply seek a place to enjoy dance and fitness. It’s a perfect blend of education, talent, skill and vision.”

The challenge, then, will be spreading the word. Alloways-Ramsey wants to increase the school’s profile by having students enter—and win—prestigious national and international competitions. Doing so, he says, “brings huge accolades” and attracts students from around the country and around the world.

The school’s Trainee and Orlando Ballet II programs—for ages 16 to 21—are preprofessional companies in which students are selected via audition. Academy and Academy Preparatory programs are also rigorous audition-only programs for serious young dancers who are at least age 13. “It’s Olympic-level training,” notes Alloways-Ramsey.

But there are also classes for children and adults who simply love to dance or wish to improve their fitness. During the school year, all children ages 3 to 6 receive combined instruction while those ages 7 and up must take a placement class and are grouped by knowledge, ability and potential.

Spring and summer camps serve children from ages 3 to 5 and 6 to 12 with full- and half-day options. There are also Summer Intensive programs for intermediate to advanced students ages 9 and up. Fitness Thru Dance classes are held year-round for those ages 14 and up and often include adults as well as teenagers.

In all, the school has about 800 students enrolled at any given time with four full-time instructors, all of whom have been certified by the American Ballet Theater. “We have a very strong faculty here,” he adds.

Alloways-Ramsey, who says as a young dancer he benefited from having great individual teachers, hopes to structure the school where only one instructor can guide each class level for one school year. That way, he adds, students won’t be exposed to as many conflicting ideas from multiple teachers.

The Orlando Ballet School is located in Harriett’s Ballet Centre, 600 North Lake Formosa Drive, Orlando, in Loch

Haven Cultural Park. For more information, call 407.418.9818 or visit orlandoballet.org.

ORLANDO MUSEUM OF ART

OMA Is Focused on the Next 100 Years

Cathryn Mattson says it’s time to move past the cloud of scandal that resulted from the Orlando Museum of Art’s exhibition of purported works by Jean-Michel Basquiat. The ensuing fallout generated (and continues to generate) national headlines for the institution even as it looks toward celebrating its 100th year.

Anyway, you know the story. And you know why Mattson—who was named permanent executive director and CEO earlier this summer after a five-month stint with “interim” in her title—says that she and her team are “working diligently every day to get the museum back on a healthy track and we’re making wonderful progress.”

Indeed they are. Attendance—which never really waned—has now surpassed pre-COVID levels. That’s due in part to the Access for All initiative, underwritten by the Bentonville, Arkansas-based Art Bridges Foundation, through which free admission is offered every third Thursday.

“There are days that the galleries are filled and the parking lot is full,” says Mattson. “That’s very gratifying to see.”

Special events are also being well supported. For example, more than 600 people attended the Florida Prize in Contemporary Art Preview Party, and more than 14,000 people attended the Council of 101’s Festival of Trees.

Most encouraging, says Mattson, is that once-wary donors are back on board and several buzzy exhibitions are en route. After the exhausting travails of the past year, it sounds like there are finally reasons to celebrate at OMA. And a celebration is exactly what’s going to happen.

A Centennial Gala—slated for Saturday, September 28 at 6 p.m.—will feature entertainment from Orlando Ballet, Opera Orlando and the string section of the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra. Attendance will be limited to 250 people with tickets priced at $450.

And don’t doubt for a minute that this event will sell out, says Mattson, who adds: “I’m focused entirely on the future.”

With an MBA in marketing and strategy from Columbia Business School at Columbia University, Mattson—a resident of Windermere—has most recently served as president of Mattson Coaching, through which she collaborates with executives and senior managers to help them more fully realize their leadership potential.

Prior to that, she was partner and COO for the Boston-based Bridgespan Group, a leading social-impact consultant and adviser to nonprofits, nongovernmental organizations, philanthropists and investors who are tackling society’s most important challenges and opportunities.

She has also served as COO for Tiger21, a premier learning group for high-net-worth investors, and Women’s World Banking, a global network of microfinance institutions dedicated to providing financial services to low-income women for entrepreneurial activity.

In addition, Mattson spent 20 years in executive leadership positions with Bestfoods and Unilever Bestfoods after their merger. “A business background helps you to address tough business challenges,” she notes. “The problems we have faced aren’t small, but they are fixable. And we are on an aggressive path to fix what needs to be fixed.”

Mattson started her career in the arts as program director for the South Carolina Arts Commission. Then she relocated to New York City to become artistic director for Young Audiences New York, which provided concerts and artist residencies for public schools in New York City. She later became executive director of the Theater at St. Peter’s, an off-Broadway venue.

At OMA, Mattson is expecting a trio of cool—and definitely unusual—exhibitions to draw new visitors and solidify the institution’s relevance in the art world, a goal shared by recently appointed Chief Curator Coralie Claeysen-Gleyzon, who first joined the museum as associate curator in 2018 and was among the insiders who voiced concern about the Basquaits.

Torn Apart: Punk + New Wave Graphics, Fashion and Culture, 1976-’86, will showcase author Andrew Krivine’s extensive collection of punk graphics and ephemera, as well as the fashion of Vivienne Westwood and photographs by Sheila Rock.

Push: J. Grant Brittain, will display the globally acclaimed photographer’s images from the skateboarding scene in the ’80s; and Front Row Center: Icons of Rock, Blues and Soul, will include photographs of such pop music icons as Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and David Bowie.

All three exhibitions—each in a different gallery—will open on September 21 and, during the course of their runs, will be accompanied by related activities and events.

Mattson’s message to the community: “Continue to support the museum. Get back in touch if you haven’t visited in a while. Judge us by our actions, accomplishments and the value that we bring to the cultural life of Central Florida. Know that we’re focused every day on earning the privilege to serve this community for many years to come.”

The Orlando Museum of Art is located at 2416 North Mills Avenue, Orlando, in Loch Haven Cultural Park. For more information, call 407.896.4231 or visit omart.org.

CASA FELIZ HISTORIC HOME MUSEUM

‘Happy House’ Again a Rogers Family Affair

When Betsy Rogers Owens moved back to Winter Park in 2001, an urgent—and ultimately successful—campaign had been launched to save the Andalusian-style masonry farmhouse that her celebrated grandfather designed in 1933.

By 2004, Owens was operating the born-again Casa Feliz Historic Home Museum property adjacent to the Winter Park Golf Course. She left in 2016 to take a job as vice president of marketing and community relations at the Boys & Girls Club of Central Florida.

But, when karma is favorable, matters of the heart have a way of coming full circle. Now Owens is back as executive director at Casa Feliz (“Happy House”), arguably the most notable of several dozen local homes still standing that sprang from the well-worn drafting board of James Gamble Rogers II.

“It feels great to be returning to a job where I’m surrounded by—and charged with protecting—my family’s architectural legacy,” says Owens, who replaces Susan Omoto, previously chief resource officer for the Historical Society of Central Florida, the support organization for the Orange County Regional History Museum.

Actually, Owens technically works for the nonprofit Friends of Casa Feliz, which leases the architectural treasure from the city for $1 per year and manages the property. The operation is self-sustaining through earned income and donations.

The home, originally commissioned by Massachusetts industrialist Robert Bruce Barbour, was the site of so many social events that it became known as the city’s “community parlor.” But nearly 70 years after its completion, new owners sought to raze the beloved but bedraggled structure and build something new.

Alarmed local residents—rallied by Jack Rogers, Owens’s father and the architect’s son (who is, himself, an architect)—made rescue of the home a cause célèbre and raised more than $1.2 million in private donations, which unlocked a matching grant from the state Division of Historical Resources. The city donated the site, while others—including Rogers and contractor Frank Roark—donated professional services.

Casa Feliz (it got that nickname in the ’60s) was moved across Interlachen Avenue to its present location, an operation that attracted national media attention as the 750-ton structure, balanced on 20 pneumatically leveled dollies, lumbered 300 yards to its new site where it was restored to its former glory by skilled artisans.

At 5,400 square feet with lushly landscaped grounds, Casa Feliz has subsequently become a combined museum/civic space where intimate concerts and business events are staged and weddings—which are the exclusive domain of Arthur’s Catering—occur on almost a weekly basis.

Owens had a successful business career prior to running Casa Feliz. She earned an economics degree at the University of Virginia and an MBA at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and served for seven years as managing director of the West Virginia Roundtable, a nonprofit CEO group in Charleston.

She got the chance to move back to Winter Park when her journalist husband was hired as an editorial writer for the Orlando Sentinel. (Paul Owens is now president of 1,000 Friends of Florida, a nonprofit advocacy group for smart growth headquartered in Tallahassee.) Three years later, she took the part-time job at Casa Feliz.

During Owens’s tenure, she promoted appreciation for the city’s architectural heritage through such events as the James Gamble Rogers II Colloquium on Historic Preservation, which was suspended during the pandemic and hasn’t been revived.

She also advocated for stricter historic-preservation requirements in Winter Park—a subject fraught with controversy in a city where residential tear downs are commonplace—through a wonky but entertaining blog with the deceptively innocuous title Preservation Winter Park.

“I think it’s important that Casa Feliz be more than just a wedding venue,” says Owens, who was previously not shy about wading into such thorny issues as how the city designates historic districts. She still isn’t shy, but is certainly more sanguine about the city’s current elected officials and their recognition that historic preservation—and protection of the city’s village scale—are important.

As for her grandfather—whose modest office is re-created on the second floor—Owens recalls him in his later years as a quiet, methodical man who squeezed his own juice from Temple oranges, swam in Lake Osceola and drove around town in a Volkswagen Beetle he dubbed Sputnik. Rogers died in 1990.

“What appeals to me most about my grandfather’s architecture is his artistry and attention to detail,” says Owens. “Nowadays, people build to impress. He didn’t. His homes are of a human scale, built to nestle into the surrounding neighborhood rather than just jut from it.”

The Casa Feliz Historic Home Museum—which was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008—is located at 656 North Park Avenue, Winter Park. For more information, call 407.628.8200 or visit casafeliz.us.

ORLANDO SHAKES

He Played ‘Orlando’ and Wed ‘Rosalind’

When Jim Helsinger was an actor in New York City, he—like all actors seeking work—routinely scoured trade publications for audition opportunities. In September 1991, he noted a brief in Backstage magazine that would change his life and define his career.

It read: “Orlando Shakespeare Festival is accepting pix and resumes for consideration for 1992 rotating repertory company productions of Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

Helsinger, who was born “among the cows and the cornfields” of Lebanon, Ohio, would land the roles of Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet and Francis Flute in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

But little did he suspect that this initial six-week gig would lead to his becoming artistic director for the promising company—and that he would spend 30 years (and counting) in that capacity.

During Helsinger’s long and productive tenure, he helped to build what is now known as Orlando Shakes into one of the region’s most acclaimed professional theaters, praised by Wall Street Journal theater critic Terry Teachout as “outstanding … spectacular … Broadway worthy … a company that deserves to be far more widely known outside Florida.”

“I also fell in love and got married through my work here,” says Helsinger of the 1993 season, when he returned to play the character Orlando in As You Like It. He still chuckles at the unlikely coincidences that appeared to confirm his ultimate destiny as a Central Floridian.

In As You Like It, his character’s name matched that of the city where he was performing. What’s more, actress Suzanne O’Donnell, his wife-to-be, played opposite him as Rosalind. That’s also the name of the street where the Walt Disney Amphitheater in Lake Eola Park—the venue for the production—is located.

The Orlando Shakes was founded as “Simply Shakespeare” by an eccentric but energetic UCF English professor, Stuart Omans, who in the early ’70s would pilot a colorful Partridge Family-style school bus filled with acting students from school to school and have the troupe treat youngsters to scenes from Shakespeare.

By 1989, development of a permanent Shakespeare Festival affiliated with UCF was a full-time job for Omans, who helped Mayor Bill Frederick persuade Walt Disney World to support the building of a new bandshell where productions could be staged on the shores of the city’s signature lake.

A board was appointed and, with financial support from UCF, offices were leased and an administrative staff was hired. Soon what was then known as the Orlando Shakespeare Festival became integral to the local cultural landscape.

(The organization was later known as Orlando-UCF Shakespeare Festival, then Orlando Shakespeare Theater in Partnership with UCF, then just Orlando Shakespeare Theater before being rebranded as Orlando Shakes in 2018.)

Thousands attended performances at the bandshell. The Young Company—a program for at-risk children—was formed, the number of performances was expanded and educational outreach programs were bolstered.

Omans stepped aside in 1994 and Helsinger—armed with an impressively detailed (and graphically mind-blowing) 10-year plan—applied for the job “with the idea of expanding it into a regional Shakespeare theater.” He was hired in 1995 as the company’s second artistic director and to teach Shakespeare at UCF.

Helsinger—who earned an undergraduate degree in theater from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and an MFA through the University of Alabama at Montgomery’s Professional Actor Training Program—also envisioned a company that would offer productions other than those written by Shakespeare.

During his first season Helsinger began “Shakespeare Unplugged,” monthly readings of the Bard’s plays with the goal of covering his entire known canon (it took three seasons).

And he staged the first non-Shakespeare offering—his own Dracula: The Journal of Jonathan Harker, in a makeshift performance space at the old Winter Park Mall (the current site of Winter Park Village).

By 1997, the company was looking for a permanent home and found one in Loch Haven Cultural Park, where a city-owned complex that had previously housed the Orlando Science Center and the Orange County Regional History Center was about to be demolished.

“I walked through and immediately called [board chairperson] Rita Lowndes,” says Helsinger. “She was very supportive of our taking this space.” A grand opening celebration of the remodeled and repurposed building, which the theater still maintains and leases from the city for $1 per year, was held in 2001.

Today, the John & Rita Lowndes Shakespeare Center encompasses administrative offices, houses four theaters—the Ken and Trisha Margeson Theater (324 seats), the Marilyn and Sig Goldman Theater (118 seats), the Lester and Sonia Mandell Studio Theater (99 seats) and the Santos-

Dantin Studio Theater (70 seats)—two rehearsal halls, a gift shop, two lobbies, meeting space, and set and costume work and storage areas.

With an annual budget of $4.2 million, Orlando Shakes has more than 30 full-time employees, as well as more than two dozen seasonal employees and interns. More than 150 artists are also hired each year for the theater’s productions.

The 2024–25 season, the theater’s 36th, will be a truncated one—four shows (instead of eight) in the Signature Series—because of a $6.5 million renovation project that will completely replace the 53,000-square-foot building’s roof and air-handling system.

The project will close the building from July through November, which will necessitate that at least the first show in the Signature Series—What the Constitution Means to Me (October 2 to 13)—be held at Orlando Family Stage. PlayFest, which features readings of new works, will be on hiatus until the fall of 2025.

Helsinger—who directs some plays, has written others and keeps his acting chops finely honed as well—says he has given little thought to his 30th anniversary and still has much more he’d like to accomplish at the Shakes, which this year welcomed a new managing director, Larry Mabrey, most recently managing director at Santa Cruz (California) Shakespeare.

For example, he’d like to finish the “Fire & Reign” series, which tracks the history of England’s monarchy through Shakespeare’s plays presented in the “original practices” style: The actors direct themselves, with limited rehearsal time and rudimentary sets, costumes and lighting—as would have been the case during the Elizabethan Era.

There’s one play in the series this season—Henry VI, Part 2:

She Wolf of France (January 8 to 19, 2025)—and five more yet to stage in future seasons. In addition, Helsinger is working on a one-man show, Shakespeare’s Clown, about Will Kempe, one of the original actors who specialized playing comedic roles in plays by Shakespeare.

And in his spare time, Helsinger adds, he’d like to adapt Great Expectations and The Count of Monte Cristo for the stage. As a playwright, he’s the author of Robinson Crusoe; A Christmas Carol in Five Parts; The Trial of Joan the Maid; and Frankenstein, the Modern Prometheus; and Dracula: The Journal of Jonathan Harker.

Orlando Shakes is located at 812 East Rollins Street, Orlando, in Loch Haven Cultural Park. For more information, call 407.447.1700 or visit orlandoshakes.org.